CHAPTER 1

Software for Civilisation

There is nothing to which nature seems so much to have inclined us, as to society.

There are many advantages for animals to living in groups. It makes finding mates much easier; it allows for successful hunting in packs; and it offers safety in numbers and protection from predators. But compared to herds of wildebeest or schools of fish, there is a great deal more complexity in human societies. We have an incredible propensity to cooperate. The key to human success has been not just our adept tool use, made possible by the dexterity of our hands, but our willingness to offer a helping hand to one another, even if we’re unrelated or unlikely ever to meet again. As Nichola Raihani puts it in her excellent book The Social Instinct, ‘Cooperation is our species’ superpower, the reason that humans managed not just to survive but to thrive in almost every habitat on Earth.’ We teach one another skills and exchange information that we would never have worked out for ourselves in one lifetime. This process of cultural learning enables the spread of new capabilities not only throughout populations but cumulatively over generations.

In this chapter, we’ll look at two major developments in human evolution that were key prerequisites for our ability to create complex, largely peaceable societies and work together in the huge enterprises that we call civilisations:fn1 the reduction in reactive aggression and the development of the social software in our brains that enables unparalleled levels of cooperation.1

TAMING OURSELVES

It is simplistic to think of aggressive behaviour in terms of a single sliding scale from docile to violent. There are two forms of human aggression which are quite distinct from each other. Reactive aggression is a hot-headed response, an impulsive lashing out against an immediate threat. On the other hand, proactive aggression is driven less by impulse and emotion: it is calculated, premeditated action towards a specific goal. Throughout our development as a species, the expression of these two forms of aggression shifted in different directions – we evolved to be very moderate with the first, but highly proficient at the second. If we view aggression as a dualistic phenomenon, we can see that there is no contradiction in saying humans can be both brutal and benign.2

Our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, live in mixed groups of males and females. These groups are fluid in their size and composition, splitting into smaller groups to forage different areas during the day, before reconvening to sleep at night. Over longer timescales, individuals move between different groups dispersed across the landscape; related chimpanzee males, for example, stick together but mate with females from neighbouring communities once they are old enough to breed.

This periodic division and reassembly of groups is known as fission-fusion social organisation. In such mixed groups of chimpanzees, outbreaks of aggression and violence are commonplace. Males harass females, and there is frequent antagonism and vicious competition between males over reproductive access to the females. Male in-fighting establishes a hierarchy, and the alpha male must use violence, or the threat of it, to maintain his position at the top. Male chimpanzees also form gangs to patrol the boundaries or their territory or invade that of neighbouring groups. They attack, and sometimes kill, males from other groups to expand their sphere and gain access to more resources or females. Bonobos are generally less violent than chimpanzees, but they also exhibit aggression both to other members of their group and to outsiders.3

While aggression is a way of life for chimpanzees, human evolution took a very different trajectory. The rates of physical aggression among other primates – even the more peaceful bonobos – are more than a hundred times higher than among humans.4 Indeed, acts of reactive anger are remarkably rare within traditional hunter-gatherer societies today. These groups are also notably egalitarian, with no despotic alpha male or strong dominance hierarchy.

The key development in human evolution appears to have been the emergence of coalitions of males to keep in check or remove any would-be tyrant. There were two key drivers of this transition in our social structure: language and weapons. The ability to communicate effectively enabled individuals to conspire and plan a coordinated move against a tyrannical top dog, while reassuring one another of their shared intent and commitment. In short, language opens up the ability to plot the disposal of a despot. And when launching such an attack, the use of projectile weapons, such as a rock or spear, permitted a decisive move without any one individual exposing themselves to great physical risk.5 Such coalitions tend to attack only when they have overwhelming numbers and are assured of victory. The same calculated mathematics of relative strength has been at the forefront of every general’s mind throughout human history.6 The first such planned killing of a despot would have happened hundreds of thousands of years before the assassination of the Roman dictator Julius Caesar in 44 BC.

The effectiveness with which individuals could join forces to safely challenge and dethrone aggressive despots levelled the playing field. An individual’s influence within society became decoupled from their personal physical might, and instead came to rest on the strength of their social network and the reputation they had gained based on their generosity or supportiveness. Power shifted, from a dominant alpha male who acquired and then maintained his authoritarian position through brute force and the threat of violence against any challengers, to the wider group in a more equitable distribution. A new kind of political system had arisen and transformed the fabric of early human communities: strict hierarchy gave way to a more egalitarian structure. This reduction in reactive aggression and increased placidity of humans laid the foundations for the development of complex cooperation and cultural learning.7

This ability for coordinated alliances to keep violent despots in check with planned proactive aggression8 created the selection pressure to reduce hot-headed reactive aggression. Unlike a chimpanzee in the prime of his strength, it no longer paid for humans to lash out at rivals in an attempt to rise to the top. Indeed, gaining a reputation for being violent only risked a coalition of opponents later rising against you. Collective punishment of reactive aggression resulted in its evolutionary suppression. We domesticated ourselves.fn2

As this shift in human social structure progressed, other, milder sanctions could be used to maintain balance within the group, without needing to resort to proactive violence. Anyone getting too big for their boots became the target of public ridicule, shaming or ostracism – we still find these patterns and rituals at work in hunter-gatherer societies today. But the threat of being attacked by a coalition of those who a dictator would attempt to dominate remained the ultimate deterrent. While the ability for a community to remove a despot does not guarantee an equitable and fair society, it is a prerequisite and goes a long way to levelling out a dominance hierarchy.

So, while hot-headed, reactive aggression was suppressed in the human evolutionary lineage, calculated, proactive aggression remained.13 Surprise attacks from one settlement or village against another were motivated by the desire to remove competitors or acquire resources or mates. The more recent extension of such behaviour, emerging with the development of city states and civilisations, is all-out warfare. Indeed, war is the ultimate expression of proactive aggression, ordered by rulers, planned by strategists and commanded in the fray of battle by generals.

In normal life, lethal violence is socially prohibited; in war, on the other hand, the very objective is to kill a decisive number of the enemy. But humans generally have a deep-rooted aversion to discharging violence upon one another – a biologically encoded peacefulness borne of our evolution within egalitarian social organisations. While leaders may try to rouse their men with proclamations about the honour and glory to be had on the battlefield – fighting for God, king or fatherland – many soldiers throughout history, many of them farmers mustered from their fields, have found the thought of killing another person utterly abhorrent. The social traits and inclinations that enabled humanity to live harmoniously in complex societies and develop civilisation must be overcome to prepare us for war. In order to induce troops to kill, military training is often directed towards increasing aggression, and propaganda aims to dehumanise the enemy.14

CIVILISATION AND THE RE-EMERGENCE OF THE DESPOT

This largely egalitarian social structure is believed to have held sway for the great majority of our history as anatomically modern Homo sapiens. But the desire for personal power and dominance never disappeared. Indeed, the conditions created by the introduction of agriculture and the arrival of the earliest civilisations led to the re-emergence of despotic supreme rulers.

In a hunter-gatherer society, the fresh meat from a successful kill, or foraged perishable plant products such as fruit, must be consumed immediately before they go off, so it makes sense to share them among the group. In any case, the group is constantly on the move and does not have the capacity to accumulate a stockpile of resources.

With the development of agriculture, humans began to live in permanent settlements alongside their fields or pastures. Farmers were no longer limited to the possessions they could personally carry. What’s more, the glut of food produced at harvest time, and the need to store the surplus in granaries, created commodities that could be hoarded. Thus was born the concept of wealth. Agricultural surplus enabled denser and denser concentrations of humanity, the emergence of cities and greater levels of social organisation, leading to more complex states and the development of civilisation.

While there is evidence that some hunter-gatherer populations were not perfectly egalitarian and did exhibit degrees of sedentism, social stratification and specialisation of roles within the community,15 it is clear that these characteristics all became much more widespread and pronounced with the advent of agriculture.

Individuals who assumed a position of leadership, perhaps through their skill in rallying peers to work together in successful shared enterprises like constructing and maintaining irrigation systems, were able to exercise authority over such vital infrastructure and accumulate resources for themselves. Those exerting control over the distribution of valuable caches of food and other assets could withhold resources to exercise leverage or use them to buy allegiance to quash leadership challenges or uprisings. And through the transmission of material riches and social rank from one generation to the next by familial inheritance (something we’ll come back to in the next chapter), initially small differences in resource wealth – and the influence and stature it affords – came to be amplified. Rulers were able to consolidate their position; privilege and power became increasingly concentrated in elite classes and the social structure ever more stratified. In an agricultural world dependent on established infrastructure and city life, people were less able to simply move away and had little choice but to put up with increasingly autocratic rulers.16

This disparity of power was only exacerbated by the innovation of the first metalworking processes and the production of bronze weapons, armour and shields. In the ancestral condition, the general availability of potential weapons – any heavy stone or pointed branch could be wielded against an enemy – fostered egalitarianism. But when superior weapons and armour are difficult to manufacture, or the raw materials rare and expensive, the effect is to bolster the dominance of the despot. Only the top dog controlling the wealth can afford to buy the loyalty of fit, strong men and equip them with cutting-edge arms technology. It becomes a great deal harder for an ad hoc coalition of individuals to remove a tyrant. Indeed, a state is often defined as a coherent polity that is able to operate a monopoly on violence within its boundaries – with the sovereign ruler controlling where and when that violence is directed.17

COOPERATION AND ALTRUISM

We have not only modified our patterns of aggression to live peaceably together in large groups, but become prodigiously cooperative and uniquely altruistic. It’s important to distinguish between the two: altruism delivers a benefit to the recipient at the expense of the donor; whereas cooperation benefits both parties. Cooperation is widespread in the animal kingdom. Hyenas working in packs to bring down an antelope far larger than themselves collectively achieve a goal that no one individual could on their own. But the sheer extent of cooperation exhibited by humans overshadows anything like that of any other species on the planet. Civilisation is itself the ultimate expression of cooperation – of large groups of people contributing to the same shared venture.

Much of the assistance that humans give one another is altruistic. This means that one individual helps another at a cost to themselves – in terms of food, energy, time or other valuable resources – seemingly with no immediate personal benefit. At first consideration, such acts appear to be difficult to explain within the context of evolution. If every individual in a population is in competition with others to survive and reproduce, what can be gained by helping another, especially at a cost to oneself?

Natural selection is often thought about in terms of an individual’s ability to survive in a particular environment, compete against members of their own species as well as others and succeed in finding food and mates. Those with advantageous traits prevail and reproduce, so in the next generation more individuals carry the particular genes that produce those traits, and over time a species adapts to become better suited to its environment. The real success of an individual isn’t just the number of progeny they are able to produce but the number of progeny that themselves survive to go on to reproduce. It’s taking the long view: fitness is about maximising the number of grandchildren you have.18

But there’s another key insight here. Selection favours not only traits that advantage your own direct descent – your number of grandchildren – but also those that contribute to the reproductive success of relatives. A particular gene propagates not only if a given individual who carries it gains an advantage, but also if related individuals – who are likely to be carrying copies of the gene – survive and reproduce. This is the concept of inclusive fitness.

By this rationale, an individual can help copies of their own genes survive and spread by assisting their relatives, in proportion to how closely related they are. More specifically, an individual’s genes will prosper if the cost incurred by the individual in helping a relative divided by the benefit received by that family member is less than their degree of genetic relatedness. This is known as Hamilton’s rule, after evolutionary biologist W. D. Hamilton, who expressed it in a mathematical formula. But it’s best understood with an example. You are 50 per cent genetically related to a full sibling – which is to say, there’s a 50:50 chance that any randomly picked gene of yours is identical in your brother or sister through descent – and provided that any action you take to help gives them at least twice as much benefit as it costs you, then it will lead to an overall advantage for your shared genes. This key realisation led evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane to quip once to friends in a London pub that he would jump into a river and risk his life to save two brothers, but not one, or to save eight cousins, but not seven.19 By helping your family members, particularly if they are close relatives, you are indirectly serving your own genes. This evolutionary strategy of assisting the survival and reproduction of relatives, even at a cost to oneself, is known as kin selection.

Apparently altruistic behaviour directed towards relatives is still self-serving, therefore, in that it helps to propagate the genes that you share. In small, close-knit communities, with little coming and going of individuals from other groups, the people surrounding you are likely to be related and so it pays to be generally helpful towards other individuals in your own group.

Kin selection is everywhere in the animal world: many species have been shown to preferentially help their immediate family, or those in their group who are odds-on likely to be related and so share many genes. What’s more, many animals, including humans, appear to possess an encoded appreciation of Hamilton’s rule: they not only behave more altruistically to kin compared to non-kin, but are also more altruistic towards closer kin than more distant relatives.20 Within human populations, kin selection expresses itself in everything from charging towards a predator to protect family, going hungry to feed siblings or helping to raise a sister’s youngsters (or diving into a river to save a particularly unfortunate group of eight cousins).fn3

Kin selection provides a neat explanation for most of the altruism we find in nature. But it cannot account for acts of generosity towards non-relatives. How can a behaviour be evolutionarily advantageous if it comes at a cost to yourself, but you cannot count on the beneficiary sharing any of your genes? The fact that, compared to other animals, humans are freakishly kind to non-relatives demands another explanation.

RECIPROCAL ALTRUISM

The theory that is generally believed to explain how non-related individuals may benefit from helping each other is known as reciprocal altruism. The idea is that if one individual helps another, even if paying a cost in doing so, the favour is returned at a later time. In this way, cooperation can evolve as a series of mutually altruistic acts.22

Such reciprocal altruism isn’t nearly as common among non-human animals as kin altruism, but there are examples in a few species that, like humans, have an ecological necessity for social interactions.23 Evidence for reciprocal exchange can be found among other primates, including baboons and chimps, as well as among rats and mice, some birds and even fish.24 One of the best-studied cases is that of vampire bats. These bats feed on the blood of large wild mammals, as well as of our domesticated livestock. But finding a meal can be difficult, and because of their high metabolism, these animals need to feed every day or two. Vampire bats live in large groups, and if one individual has successfully fed it will often regurgitate blood to share with a less fortunate colony-mate. A bat that altruistically shares blood one night is likely to have the favour returned another day when the tables have turned.25

There’s a simple economic principle lying at the core of why reciprocal altruism works so well. Those who successfully gathered food often have acquired more than they need to survive. The surplus becomes less valuable, making only a marginal difference to their prospects. But for an individual that does not yet have enough to eat, that extra unit of food is still very valuable – it could mean the difference between life and death. So a benefactor can donate some of their surplus to someone in need at minimal cost to themselves but huge benefit to the recipient. In the case of the vampire bats, one feast on an animal supplies more than enough sustenance and so an individual who successfully foraged has food to bestow on another, less fortunate bat who may otherwise have starved to death. Later, when fortunes have shifted and the original recipient has a surplus, they can return the favour, again with the greatest possible utility being extracted. Thus reciprocal altruism is a form of asset exchange, and each donor can receive a profitable return on their investment.

By engaging in this practice, both parties have extracted the maximum value from a surfeit they possessed at different times. For this reason, the behaviour is often also called delayed altruism. Competition is said to be a zero-sum game: for one individual to gain, another must lose. But cooperation is non-zero-sum: both sides can profit from the arrangement and often substantially so. This dynamic is utilised by both vampire bats and early humans sharing food and other resources or performing a service for one another. As Raihani points out, ‘Reciprocity is so fundamental for driving cooperation that it has become enshrined into well-known proverbs. Quid pro quo. You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours. Do as you would be done by. One good deed deserves another. These maxims exist in other languages too. In Italian, una mano lava l’altra translates into the particularly lovely “one hand washes the other”, a phrase that also exists in German (ein Hand wäscht die andere). In Spanish, hoy por ti, mañana por mi means, roughly, “today for you, tomorrow for me”.’26

The problem with altruistically providing resources or services willy-nilly, helping others when you can’t be certain that they will reciprocate in the future, is the risk of being played for a sucker. Cheaters can take advantage of your indiscriminate generosity, and you end up paying all the costs of helping but receive few benefits back. For the system to work, freeloaders must be held in check: those who don’t reciprocate need to be punished by being refused help next time so as to incentivise mutually cooperative behaviour. If the recipient refuses to repay the kindness when fortune swings in their direction, the original altruist needs to remember and desist from helping them again in the future: once burned, twice shy. This tit-for-tat behavioural strategy is also found in some animals: ravens, for example, have been found to refuse to help other individuals who cheated in the past.27

FRIENDSHIP AND THE BANKER’S PARADOX

Keeping a mental ledger on which individuals did or did not reciprocate favours carries its own cognitive burden, however, and human evolution has devised a solution to this. After repeated rounds of reciprocation with the same individual we begin to relax our monitoring of the exchanges. In other words, we come to trust one another, and the relationship develops into a deeper bond: friendship. A friend serves as a trusted collaborator and ally in other social interactions, and we suspend the mental accountancy on keeping track of their behaviour and no longer explicitly expect or demand any particular favour to be repaid. The bond is its own assurance of reciprocity and an investment in the future.28 We know that friendships sour, of course, but only after a long history of one partner taking more than they give back.

The bond of friendship is biologically mediated through oxytocin, the hormone that serves in all mammals to drive maternal care of their young, and in humans sustains the pair-bond between sexual partners long enough to successfully raise children together (which we’ll come back to in Chapter 2). Friendship among humans is an extension of this close-knit relationship between parents and their offspring: we also forge a tight bond to those with whom we regularly reciprocate. It is this neurochemical bond that makes the pain of betrayal by a close friend so much more intense than the vexation of being cheated by a stranger.

In particular, the bond of friendship may solve a problem known as the banker’s paradox. When you are facing financial ruin and most need a loan, the bank is unlikely to grant you one as you represent a terrible credit risk. On the other hand, when things are going well the bank is only too happy to offer you funds. This same dynamic would also have posed a deep problem for reciprocal altruism in the world of our ancestors. Individuals may be least likely to receive help when they most need it, because they are least able to reciprocate. Why would a non-relative come to your aid, with a greatly reduced chance of being paid back the favour? The evolution of friendship provides a solution to the quandary. The oxytocin-mediated bond between friends makes them irreplaceable to each other. So if a friend falls seriously ill, rather than callously abandoning them to find someone else with whom to engage in reciprocal altruism, you have an emotional stake in their well-being that compels you to help them pull through. A friend in need is a friend indeed. In this way, friendship may have developed in human evolution as a form of insurance against desperate times.29

There are a few known examples of reciprocal altruism in the animal world – such as among the vampire bats – but the practice is exceptionally common among humans. It accounts for a great deal of the generosity and cooperation seen in our interactions, especially within small, tight-knit societies where individuals have a high probability of encountering one another again so altruistic deeds can be repaid. But one extraordinary feature of human behaviour, compared to all other animals, is our propensity for helping each other even when there can be no expectation of regular interactions. This is the kindness of strangers. Humans often ungrudgingly offer assistance even to those they have never met before and can have no great expectation of ever encountering again. How can such one-off acts of kindness be explained? Kin selection and reciprocal altruism cannot account for this behaviour; there must have been other things at work in the development of our species.

One possible explanation is an evolutionary mismatch. The ancestral human condition was life in small bands with most individuals related to one another. Under these circumstances, kin selection and reciprocal altruism can comfortably explain generous acts between tribemates: you’re either directly helping copies of your own genes or repeatedly interacting with the same individuals for a favour to be returned. But this simple evolutionary strategy would have no longer worked so well as humans began living in larger, more complex societies, particularly when ever-greater populations settled in urban environments, dominated by fleeting interactions with strangers with no familial connection. On my morning walk into work, I pass more strangers on the street than my hunter-gatherer ancestors probably encountered in a lifetime. Yet in general we continue to cooperate with those around us, even though there is no longer any genetic self-interest.

Our minds evolved to drive behaviour that was adaptive in our ancestral conditions, in small, kin-based communities on the African savannah, and this cognitive operating system has not had a software update as the social environment has rapidly transformed. Thus our altruistic dispositions are not calibrated to our evolutionarily novel world. This produces the apparently maladaptive behaviour of helping strangers when the favour will never be returned by them. 30

But there’s a better explanation for why humanity is so prolifically cooperative without an expectation of direct reciprocation – and it actively explains this apparently paradoxical behaviour rather than just seeing it as an evolutionary programming hangover.

INDIRECT RECIPROCITY

The notion of indirect reciprocity holds that rather than returning a favour to the same altruist, the benefactor pays it forward to others. A helps B, who then helps C, who then helps D and so on. The favour is transferred around the community, until sooner or later it returns to A. What goes around comes around. And there’s an additional level: another individual who witnessed A’s initial act of kindness towards B helps A themselves in order to build a relationship with somebody they know to be generous: Z helps A. The same two individuals don’t need to encounter each other again, as is required for direct reciprocity, but benefit from the altruistic behaviour of the group as a whole. Helpful people are themselves more likely to receive help, whereas freeloaders who refuse to help others are punished or excluded.31 Such indirect reciprocity is a uniquely sophisticated form of human cooperation,32 and for the system to work, it needs two crucial functionalities not possessed by other animals.

Firstly, not only must there be witnesses observing interactions, and whether either party acts generously or selfishly, but that valuable information on the behaviour of individuals must be shared in a common pool of information for the entire group. In other words, members of a community must gossip about one another. If an individual becomes known for unreliability, for selfishly accepting benefits and not helping others, members of the community will simply withhold aid the next time the swindler is in need. It’s not quite true that ‘cheats never prosper’ – they can often get away with it in the short term, especially in larger, more anonymous communities – but they are caught out sooner or later and their reputation is stained. Gossip, therefore, is a key prerequisite for ensuring indirect reciprocity doesn’t become overburdened by freeloaders, and its omnipresence in human cultures spans from the campfire to the water cooler. Indeed, gossip and chit-chat came to replace other relationship-forging activities in primates, such as grooming.

This prolific sharing of information throughout the community on each member’s behaviour – like a social internet mediated by chit-chat – creates a reputational system for determining every individual’s suitability for cooperation attempts. An individual who acts generously to others develops a good reputation; an unreliable freeloader gains a bad reputation, and others know to avoid them in future interactions. Natural selection favours an individual who acts kindly because others are inclined to help them later, and so evolution has crafted human psychology to makes us care deeply about our reputation, while gossip keeps us playing fair.

The first rule of life in a gossiping society is to be careful what you do – or, more importantly, to be careful about what others will think about what you do.33 Human society thus became a crowd of minds simulating other minds – inferring the motivations and attitudes of others and how they are likely to perceive your actions so that you can better manage your reputation. Our conscience is an expression of this – it’s our inner voice that warns us someone might be watching and makes us consider how they would likely perceive our action so that we can avoid social punishment.34

The second crucial facilitator of indirect reciprocity is the punishment of cheats. In the repeated one-on-one interactions of direct reciprocation we looked at earlier, an individual remembers if another person cheated them previously and so can refuse help next time. Chimpanzees are also known to take revenge for acts that personally disadvantaged them.35 However, a behaviour unique to humans is a party who wasn’t directly involved in an exploitative interaction punishing the cheat for no material gain to themselves – something that is known as third-party, or altruistic, punishment.36

Altruistic punishment behaviour in humans can be explored with simple economic games. The kind I’ll discuss here involves a group of players contributing to a collaborative outcome that is advantageous to all – what is known as a public good. Such cooperative endeavours are ubiquitous in human societies, from hunting a large kill to digging and maintaining a channel system to irrigate farmers’ fields to constructing a municipal building. The history of civilisation is the history of people contributing to public goods, and as civilisation has advanced, the number and complexity of public goods has increased accordingly.37 Cities and states provide services such as decent roads, a clean water supply, emergency services, public education, healthcare, law and order and national defence. The outcome can be enjoyed by the entire community, but only those who participated bore the costs.

Public goods are vulnerable to being undermined by slackers who may get away with putting little to nothing towards the shared venture but still reap the rewards. The public good game is often set with each player having a pot of money, and in each round of the game they can choose how much to contribute to a communal pool. At the end of the round, players pocket what they had kept behind in their personal pot, and the shared pool is multiplied by some factor (between one and the number of players) and distributed evenly among everyone. The best possible outcome for the group as a whole is for all players to contribute their entire pot so that everyone maximises the multipliable funds and thus their individual returns. But a free-riding player can profitably cheat on the cooperative effort and pitch in nothing – keeping not only their own entire pot but also the dividend of everyone else’s generosity.

What tends to happen is that most participants contribute about half of their personal pot to the shared pool – a reasonable, cautious approach. However, as the players realise that some of their number are putting very little into the shared pool, or even nothing at all, everyone’s contributions decrease round on round towards zero.38 The cooperative venture collapses under the self-serving actions of freeloaders.

But there’s a simple modification to the rules of the game that can enforce cooperation and rescue the shared venture to everyone’s benefit. The addition of a sanctioning system allows players to spend some of their own game money to reduce the income of those they felt had cheated – for example, they can pay £1 to reduce a cheat’s take-home by £3. The inclusion of such altruistic punishment radically changes the dynamics of the game. Now the individual contributions towards the common good tend to rise – sometimes to over 70 per cent of each individual’s pot – and remain at that level round on round. It seems that people are willing to incur a personal cost to punish cheaters, and this altruistic punishment is very effective at both deterring free-riders and encouraging greater cooperation among the group as a whole. And so in real life too, inveterate cheats whose selfish or antisocial actions sabotage the community risk punishments including the denial of benefits, social exclusion or ostracism – or may even become the target of proactive violence.

The key motivation driving altruistic punishment seems to be innate and emotional – players report feeling indignation or anger towards the free-riders and an impulsive desire to punish them.39 Studies have found that the righteous punishment of cheats triggers the same surge of the neurochemical dopamine in the reward centres of the brain as crucial biological functions such as sating hunger or thirst, having sex or providing parental care. (We’ll come back to the dopamine system in Chapter 6.) It is this rush of dopaminergic pleasure that drives us to shoulder the costs of delivering deserved punishment to others.40 In humans, it would seem, enforcing cooperation and prosocial behaviour has its own innate reward.41 On top of our primal urges directed towards survival and reproduction, therefore, are layered more recent neurological compulsions for our extraordinary prosocial behaviour. Humans appear to be hardwired with cooperation as the default state, and they demand fair play in interactions. Cooperation is in our coding and altruistic punishment is the glue that holds societies together.42

For indirect altruism to function in a society, the burden of administering such punishment must itself be shared among all members of the group. So we take things one step further still and also punish those who shirk the responsibility of sanctioning transgressors (and who are themselves therefore effectively free-riding on the reputational system).43 Humans are not just altruistic; we are vigilant enforcers of altruism.44 Altruistic punishment is a necessary condition to prevent cooperation being undermined by free-riders and explains how indirect reciprocation evolved in the first place.45

Indirect altruism demands sophisticated cognitive abilities. Not only does the reputational system require language and the sharing of information through gossip on which individuals have proven themselves reliable or unreliable cooperators, but each individual in the group needs to keep a mental ledger of how reputable is each of their peers in the community.

Humans have a finite capacity for keeping track of all this social data, however. The suggested cognitive limit for the number of long-term social relationships that an individual is able to maintain (which thus also limits average group size), known as Dunbar’s number, after the British anthropologist Robin Dunbar who first proposed it,46 is usually estimated to be around 150.fn4 We have a few very close, trusted friends and relatives, and outside this core group, we surround ourselves with progressively larger concentric circles of individuals we know to lessening degrees, down to acquaintances that we interact with only rarely. The numbers within each of these circles seem to remain fairly constant, so that if we make a new friend, we tend to lose contact with an old one we haven’t seen in a while. This layered structure of our social networks has been identified in different modern societies49 and is evident in who we call or text on our phones and how often,50 how we interact on social media51 and even how we play online games.52 Although our modes of communication have changed with new technology, our Palaeolithic brains have not.

In larger societies, it is these personal social networks, existing as fuzzy-edged, over-lapping domains within the total population, that foster clusters of altruism and cooperation within a world of strangers.

DETECTING CHEATS

As well as experiencing an innate impulse to punish those who break the rules on reciprocating altruism or cooperation, humans are adept at detecting instances when such infractions occur. The importance of catching cheats is so central to protecting our cooperative social life that we have developed a particularly sensitive ability to identify when rules have been broken.

We don’t normally fare very well at tasks involving the application of logical rules. A classic puzzle used to explore this is known as the Wason selection task.53

Imagine you are sat at a table with four cards laid out in front of you, as shown below. Each has a number printed on one side and is coloured either black or white on the other side. You are told that if a card bears an even number then its opposite face is white.

Which card or cards must you turn over in order to determine if the rule is true or not? This demands what is known as falsification-based logic – to find the truth, you must try to prove that a conditional rule (if p then q) has been broken.

The correct answer is that you need to check both the card showing the ‘4’ and the one with a visible black face. Turning over either the card with a ‘7’ or the card with a white face is in fact irrelevant to the puzzle – even if they do bear the ‘wrong’ reverse face, it doesn’t falsify the rule, since the rule doesn’t say that cards with odd numbers can’t also have a white back, for example.

If you got this wrong, don’t worry: you’re firmly within the majority. Only around 10 to 25 per cent of people presented with this problem get it right.54 Most recognise that finding confirmatory evidence of q in the presence of p – i.e. that the reverse face of the ‘4’ card is indeed coloured white – is important; but they don’t turn over the black card to look for falsifications of the rule – a p (even number) without a q (white face).

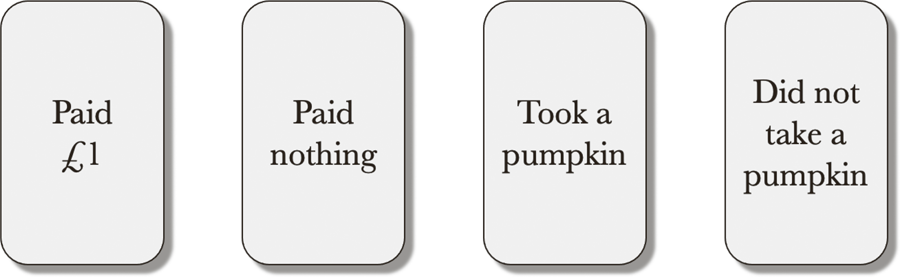

But, amazingly, if the same logical test is couched in terms of detecting cheats in a social exchange – if you take the benefit, p, then you must pay the cost, q – people perform a great deal better.55 Let’s say that a local farm has a table by the side of the road with pumpkins priced at £1 each; there’s an honesty box that you can drop your coins into. The cards for this puzzle are shown below: one side displays what an individual paid, the other whether they helped themselves to a pumpkin or not. Which would you turn over to check whether the individual represented by each card had cheated the honesty system?

In this case, the puzzle seems pretty straightforward, facile even. But it represents exactly the same process of falsification-based logic operating on a conditional rule that we encountered in the earlier example. I suspect that you, like me, would immediately reach to check the reverse side of the ‘Paid nothing’ card to discover whether the individual dishonestly took a pumpkin anyway, but also the ‘Took a pumpkin’ card to see if they had paid the required pound. We seem to intuitively know how to verify the rule of ‘if you take the benefit (p) then you pay the cost (q)’. When the Wason selection task is framed as a social exchange, 75 per cent of people give the correct answers – a rate over three times higher than for the abstract version with numbers and colours.56

Perhaps it’s not a complete surprise that people perform better at this task when it is framed in terms of a real-life, familiar scenario. But even when the Wason test uses everyday concepts – though importantly not related to fair play – people still perform badly. Yet children as young as three, when presented with the challenge in an age-appropriate pictorial form, correctly identify ‘naughty’ people violating social exchange rules by taking a benefit without meeting the requirement.57

Some psychologists and anthropologists argue that this demonstrates humans have an innate, specialised ‘cheater detection’ module in our brains which has been tailored by evolution to detect violations of fair, cooperative behaviour.58 The claim is controversial, however, and difficult to prove,59 but what is clear is that humans are especially good at catching free-riders, and this has been a critical facility in enabling widespread cooperation in large societies.

FROM SOCIETIES TO CIVILISATIONS

Evolution has equipped us with a set of internal drives that motivate beneficial behaviour: a mounting feeling of hunger compels us to eat; sexual desire and the prospect of orgasm incentivise us to reproduce. Evolution has also moulded our tendencies to promote behaviours that brought us advantages in living together in groups. These biologically encoded responses – which we perceive as emotions – include affection for family and friends, sympathy for those who are suffering, indignation and anger towards cheats, and the warm glow of satisfaction from performing an altruistic act or delivering righteous punishment. Other emotions promoting social cooperation are self-directed. Distressing feelings of guilt and remorse suggest we have acted unvirtuously, and expressing these feelings to the community can serve to mitigate the social punishment and help pave the way to mending relationships and being forgiven.60 These emotions are deeply embedded in our cognitive software – they were probably already in place in some form before our divergence from the chimpanzee lineage – and they promote altruism, reciprocity, cooperation and fairness as the building blocks of human morality.61

Morality provides a critical framework for living harmoniously in social groups. Most people around the world would agree that helping others, keeping promises and remaining faithful to your spouse are moral behaviours, whereas murder, rape and deceit are immoral.62 In broad terms, immoral behaviour can be defined as advancing one’s self-interest at the expense of other individuals, including committing an act without their consent or removing their agency to make their own free choices. Most of what we consider moral behaviour is that which is unselfish and conforms to fairness and cooperation in social exchanges so as not to destabilise society.63 The core of moral behaviour is the Golden Rule, ‘Do as you would be done by’, which requires an individual to consider their actions from another person’s perspective.

These innate human impulses promoting altruistic and cooperative behaviour, and the sense of morality that grew from them, maintain prosocial behaviour in small communities. But as group sizes grow, monitoring cooperation becomes more difficult. Direct reciprocity becomes less effective because cheats can keep finding new marks and not face punishment from a repeated interaction. Indirect reciprocity also breaks down because within bigger groups information can be slow to diffuse and it’s harder to keep track of people’s behaviour. Relative anonymity in large populations allows cheats to keep ahead of their own bad reputation.

A society can only grow so large before the innate mechanisms promoting prosocial behaviour in humans become insufficient and cooperative endeavours risk collapsing altogether under the burden of cheats and freeloaders.64 In order to enable the large populations of cities and civilisations to exist more peaceably, cultural constructs have emerged to supplement the biologically evolved drivers for cooperation.

Religion, and the belief in gods, is one such cultural innovation that has had a huge influence since the origin of civilisation. Gods have been invoked as many things in human cultures: creators of the Earth and the cosmos; causes of natural phenomena; interventionists in events both propitious and disastrous; and determinants of individual fate and fortune. But it is their role as all-seeing observers and all-powerful disciplinarians (as well as mediators of forgiveness) that serves as a powerful incentive for prosocial behaviour in large communities where transgressions may otherwise go undetected. An omnipresent, omniscient and omnipotent god serves as an ultimate third-party punisher of immoral acts. While belief in supernatural beings and religion is not necessarily a prerequisite for forming large and complex societies and civilisations, it certainly helps.fn5

The invention of writing coincided with the emergence of the first city states. Writing is a technology that seeks to overcome the limitations of human memory and oral communication for transmitting knowledge throughout society and down the generations. The first writing systems used in Mesopotamia served to record details of civic administration and trade around the fourth millennium BC; in Egypt and Mesoamerica, it was used to create calendars and chronicle the history of political and environmental events. Crucially, writing was co-opted by the state for establishing codified laws. The earliest known written codes are from Mesopotamia. Surviving fragments of the codes of Ur, a Sumerian city-state, from the third millennium BC provide a list of punishments for different crimes in the form of ‘If … then’ conditional rules. The punishment for agricultural crimes was fines in barley; fines of silver were prescribed for bodily harm; robbery, rape and murder, however, were capital offences. The Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon, from around 1750 BC is particularly well preserved and consists of over 4,000 lines of cuneiform text inscribed into a stone stele that was displayed in public. It covers areas of law including family, property, trade, assault and slaves, again written as ‘If … then’ conditional rules. Provisions include: ‘If a man should blind the eye of another, they shall blind his eye,’ and ‘If a man breaks into a house, they shall kill him in front of that very breach.’66

Most actions which have been proscribed by systems of law around the world and throughout history are those which our evolutionarily forged, collective sense of morality already denounces. These are crimes against other people and their belongings, such as assault, murder, rape, and theft or damage of another’s property. They prohibit slander – that is, falsely harming another’s reputation – as well as reckless or negligent behaviour. The Code of Hammurabi, for example, contains the somewhat draconian law that if a builder constructs a house that is not firm, and it collapses and kills the inhabitants, the builder shall himself be put to death. Then there are more recent crimes of non-compliance, such as failure to pay taxes – and thus cheating in the public good that is society itself. Non-compliance crimes are sometimes referred to as victimless, in that no specific injured person can be identified, but they potentially harm everyone in society.

Fundamentally, therefore, legal systems alter the social environment in order to modify human behaviour. They further incentivise prosocial attitudes in large societies of strangers by making it more likely that cheats are caught and penalised. Law is a tool to move humans to behave in ways they may not have if they believed they would get away with it.67 Courts emerged to establish culpability and issue punishments such as fines, imprisonment or, for the worst social transgressions, capital sentences. More recently, police forces formed to detect wrongdoing and enforce the laws. Cheater detection and punishment still requires a collective cost to be incurred, but today every member of society contributes to the public good by paying taxes, and these are used to pay the salaries of police officers, court officials and prison guards.

In situations when the rule of law was not reliably enforced, the ancient system of trust based on an individual’s reputation was extended to institutionalised reputational systems. In The Social Instinct, Raihani gives the following example. ‘Traders in the eleventh century faced a dilemma when it came to selling their goods overseas: they could personally travel with their wares and sell them on the foreign market themselves, or they could entrust the task to a foreign agent, who would sell the goods on their behalf. The latter was a more efficient option – but carried the attendant problem of trust: how could a trader be sure that the foreign agent wouldn’t just take the goods and clear off with them? The solution came in the form of merchant guilds, such as the Maghribi traders – a club that only admitted the most trustworthy members of society. By choosing to do business with a member of the Maghribi guild, a trader could be sure that his partner was committed to doing honest business. A Maghribi trader would face the much larger cost of being excluded from the guild if he didn’t toe the line. People intuitively trust the drivers of London’s famous black cabs for the same reason.’68 The threat of being stripped of their prestigious licence far outweighs the short-term gain of swindling a customer out of a few quid. Today, the use of reputational systems for facilitating transactions between strangers has gone digital, with the burgeoning online peer-to-peer economy being supported by the practice of providing public reviews and star-ratings on online marketplaces and service-providing platforms (such as AirBnB, Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit).69

The key question explored in this chapter relates to the intrinsic aspects of human nature: are we innately peaceful or violent? Two famous philosophers, Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, held opposing views on the issue. Writing in the mid-seventeenth and mid-eighteenth centuries respectively, neither had the archaeological or anthropological evidence available today regarding how our ancestors lived in the distant past, so they postulated on the lifestyle of ancient humans before the arrival of civilisation. Hobbes believed that our natural condition was a precarious existence on the brink of survival, with humans in a perpetual struggle against each other and in constant danger of a violent death, before the emergence of a powerful state – Hobbes called it Leviathan – brought this barbarity under control. Rousseau, in contrast, argued that violence is not an intrinsic aspect of human behaviour and that our ancestors lived in idyllic harmony with each other and their bountiful environment, with no need for conflict. Humans, he reckoned, are naturally good; it is large, organised societies that have corrupted us.

As is so often the case, the truth appears to lie somewhere in the middle of this dichotomy. As we’ve seen, over our evolutionary history we domesticated ourselves and developed to repress reactionary aggression. Coalitions of individuals used the threat or, if necessary, the actual delivery of proactive violence to oust despots. Hunter-gatherers lived in largely egalitarian communities, although violent conflict frequently occurred between groups. The emergence of settled agriculture meant that property could be hoarded, which soon resulted in increasing disparities of wealth and power and the appearance of severely hierarchical social structures, which allowed the strong to exploit the weak. But the top-down control and monopoly of violence exercised by emerging states also fostered more peaceable existence in larger populations, and although states waged war with one another, the coalescence into larger polities and empires maintained greater order and reduced conflict within them.70

The crucial engine that enabled humans to work well together in ever-larger, more complex societies, eventually leading to the establishment of entire civilisations, was a progression of increasingly sophisticated systems for fostering altruistic behaviour and cooperation between individuals, as well as safeguarding against freeloaders. Kin selection functions perfectly within small groups of interrelated families. Direct reciprocity broadens the scope to also support cooperation between non-kin. And indirect reciprocity enables cooperation in even larger groups, facilitated by reputational systems, third-party punishers, and trust established among social networks within the wider population. All this is enabled by the social software that has evolved within our brains. But it is not enough to support larger societies, so civilisation must be held together by cultural inventions laid on top of our intrinsic sociality and desire for cooperation – such as religion, formalised codes of law, state-administered monitoring and punishment of wrongdoers, as well as institutionalised reputational systems such as merchant guilds.

While cooperation among peers had enabled coalitions to remove tyrants earlier in our history, the social structure within civilisations became increasingly stratified. Individuals came to amass material possessions and exert control over the vital agricultural infrastructure and the distribution of resources, and so were able to buy allegiance and quash uprisings. Initially small differences in dominance became amplified and fixed. Other cultural developments, such as the forging of metal weaponry and armour, further concentrated the use of force, and states were able to establish a monopoly on violence within their boundaries and keep their subjects in check. Those at the top of the social pyramid could consolidate their position, and leaders became rulers became despots. And with the familial inheritance of material wealth and social status, the configuration of privilege and power was passed down the generations.

It is the influences of the family in human history to which we will now turn our attention.